#Industry News

Application and Considerations of MLH1 Gene Methylation Detection

Application and Considerations of MLH1 Gene Methylation Detection

Preface

The methylation of the MLH1 gene promoter region is a common epigenetic alteration in colorectal cancer (CRC) and endometrial cancer (EC), leading to gene silencing and subsequent microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Typically, high levels of MLH1 methylation are considered sporadic events in cancer and its detection is deemed a useful tool for distinguishing sporadic and hereditary diseases (Lynch syndrome). There are also some extended applications of MLH1 methylation in the diagnosis and treatment of endometrial cancer.

Application of MLH1 Methylation in Lynch Syndrome Screening

Lynch syndrome, also known as hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome (OMIM 120435), accounts for approximately 2% to 4% of all CRC cases and 3% to 5% of all EC cases. It is caused by germline mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, and is associated with MSI-H in tumor tissue. Lynch patients have a higher risk of developing CRC and EC (up to 80% and 60% respectively) and are also at risk for other types of cancer (such as gastric cancer, small intestine cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and ovarian cancer). Variations in MLH1 and MSH2 genes account for the majority of Lynch syndrome cases, with incidence rates of 40-50% and 40-60% respectively, while the incidence rates of MSH6 (10-20%) and PMS2 (2%) are lower.

In clinical practice, MMR protein immunohistochemical testing is generally recommended as a priority for Lynch syndrome-related tumor patients. When MLH1 protein loss occurs, MLH1 gene promoter methylation or BRAF V600E testing (only applicable to CRC) is commonly used to interpret sporadic tumors. The BRAF V600E pathogenic mutation is only found in 69% of methylated CRC, so the absence of BRAF V600E mutation does not exclude MLH1 methylation. The frequency of BRAF gene mutations in EC patients is extremely low and unrelated to MLH1 gene promoter methylation, so screening for Lynch syndrome does not require testing for BRAF V600E mutation.

Screening algorithm for Lynch syndrome in EC patients recommended by the Manchester Consensus

Although methylation of the MLH1 promoter and germline MLH1 mutations are generally considered as two mutually exclusive mechanisms, there are still some rare cases where highly methylated MLH1 is observed in individuals with pathogenic MLH1 germline mutations or carriers of epimutations. Systemic MLH1 methylation may represent a secondary hit silencing MLH1 in Lynch syndrome. A recent study in Italy investigated 56 Lynch syndrome patients using high-throughput sequencing (NGS) and methylation-specific multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MS-MLPA) techniques. Among patients with pathogenic MLH1 germline mutations, 16.7% (3/18) of colorectal cancers (CRC) and 40% (4/10) of endometrial cancers (EC) showed highly methylated MLH1 promoters. Although this is only a single study with a limited number of cases, it underscores the importance of considering patients' family history and personal medical history. When Lynch syndrome is strongly suspected clinically, regardless of MMR status, testing for Lynch syndrome-related gene germline mutations should be performed for confirmation.

Application of MLH1 methylation in endometrial cancer prognosis

MLH1 gene promoter methylation is associated with the prognosis of endometrial cancer (EC). A study in Japan analyzed 527 EC samples using immunohistochemistry and MS-MLPA, of which 419 cases (79.5%) were proficient mismatch repair (pMMR), 65 cases (12.3%) were suspected Lynch syndrome (loss of MSH2/MSH6 proteins or loss of MLH1/PMS2 proteins but MLH1 not methylated), and 43 cases (8.2%) were met-EC (loss of MLH1/PMS2 proteins and highly methylated MLH1). Compared to suspected Lynch syndrome patients, EC with MLH1 methylation had significantly worse prognosis.

Survival analysis of each subgroup

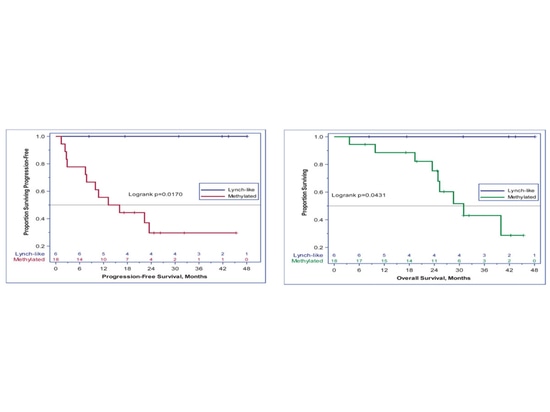

MLH1 methylation is also associated with the prognosis of EC immunotherapy. A single-arm, open-label phase II study (NCT02899793) evaluated the efficacy of pembrolizumab in recurrent dMMR/MSI-H EC patients, with a dose of 200 mg Q3W intravenous injection for 24 months. The primary endpoints were ORR according to RECIST v1.1 criteria and adverse events, while secondary endpoints included PFS and OS. Nineteen patients had MLH1 promoter methylation, six patients had Lynch-like tumors, one patient had both, and there were no Lynch syndrome patients with germline mutations. At a median follow-up of 25.8 months, the ORR was 100% in Lynch-like patients compared to only 44% in methylated patients (p=0.024). The 3-year PFS was 100% compared to 30% (p=0.017), and OS was 100% compared to 43% (p=0.043).

Waterfall plot of tumor response

Survival analysis between subgroups

Application of MLH1 methylation in molecular subtyping of endometrial cancer

Although methylation of the MLH1 gene promoter is not a marker for molecular subtyping of endometrial cancer (EC), it also plays a suggestive role in molecular subtyping, especially when the results of different methodologies are inconsistent. This point was argued in an article recently published by the Pathology Department of Peking University Third Hospital in the Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology titled "Comprehensive evaluation of mismatch repair and microsatellite instability status in molecular subtyping of endometrial cancer." The article analyzed 214 cases of EC patients using MMR immunohistochemistry and NGS (non-fluorescent products). For patients whose MMR-IHC detection results did not match MSI-NGS detection results, further MSI-PCR detection and MLH1 gene promoter methylation detection (fluorescent products) were performed.

Among 40 sporadic MMR-d type EC patients, loss of MLH1 and/or PMS2 protein expression was observed in 31 cases, among which 20 cases showed MLH1 gene promoter methylation, 1 case did not show methylation, and methylation detection was not performed in 10 cases due to insufficient tumor tissue.

A total of 9 patients had inconsistent results between MMR-IHC and MSI-NGS detection, mainly including patients with shared loss of MLH1 and PMS2 protein expression or subclonal loss. Among these, 6 cases showed MLH1 gene promoter methylation. Among the 3 patients whose MSI-PCR verification results were MSI-L, 2 patients had higher TMB values and had MLH1 gene promoter methylation, thus also classified into MMR-d. One patient did not undergo MSI-PCR detection due to insufficient DNA sample quantity, but combined loss of MLH1 and PMS2 protein expression was observed, and MLH1 gene promoter methylation was detected, which also met the criteria for MMR-d classification.

Detailed analysis of inconsistent detection results between MMR-IHC and MSI-NGS

MMR-IHC and MSI-NGS test results inconsistent commonly seen in MLH1 gene promoter highly methylated status leading to concurrent loss of MLH1 and PMS2 protein expression or MMR protein subclone loss. MLH1 gene methylation testing should be combined as necessary to comprehensively evaluate MMR and MSI status and provide accurate molecular subtyping for EC patients.

Summary

For EC with MLH1 protein expression loss, MLH1 gene promoter methylation testing helps clarify tumor MMR and MSI status, exclude Lynch syndrome risk, indicate prognosis of EC, assist in selecting treatment plans, and also provide supplementary hints for molecular subtyping.

References

[1] NCCN Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Colorectal Cancer 2023 v2

[2] 2019 Manchester International Consensus Group recommendations: Management of Lynch syndrome gynecological tumors

[3] Chinese expert consensus on molecular testing for endometrial cancer (2021 edition)

[4] Genes (Basel). 2023 Nov 9;14(11):2060.

[5] J Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Nov;32(6):e79.

[6] Cancer. 2022 Mar 15;128(6):1206-1218.

[7] Chinese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology October 2023; Vol. 58, No. 10